Expendable Men and Modern Women in Frozen

So I have finally got around

to viewing Disney’s 2013 animation Frozen

(Chris Buck and Jennifer Lee, 2013). Let me say up front that it took me

two attempts to get through the film, because I am, for the most part, not a fan

of musicals. Also be aware that in the pursuit of an informed critique of gender and feminism, this

film review contains numerous spoilers.

Frozen transforms

Hans Christian Anderson’s classic fairy tale about a villainous The Ice Queen, into a nuanced account of

how social prejudice drives desperate people to commit (what are perceived to

be) harmful or immoral acts. The film begins with an unfortunate childhood incident

when Princess Elsa accidently harms her little sister Princess Anna, when she

misdirects her magical power to conjure up ice and snow. This sets the scene

for Elsa’s isolation and her life-long quest to suppress the emotions that regularly

set off her strengthening powers. Fast-forward a number of years, the girls

have come of age, their parents have died and the coronation of Elsa as Queen

is immanent. At the coronation emotional turmoil leads to the public exposure

of Elsa’s powers, which in turn catalyses a series of events including her

self-imposed exile in the wilderness, the onset of an eternal winter, and

Anna’s desperate attempts to reconnect with her sister and undo the environmental

disaster.

What I want to zero in on

here is the very interesting subversion of normative gender roles by Disney, whose

fairy tale adaptations have historically emptied original narratives of their

sophisticated accounts, of young girls negotiating a moral minefield to emerge

experienced and worthy women. Within the Disney canon, feminine agency has

largely been the province of the bitter and twisted villainess; the good girl

is distinguished by her willingness to wait patiently for a strange prince to

rescue her from the maws of certain doom (think Snow White, Sleeping Beauty and Cinderella).

But wait you say, the 1990s

ushered in a period of Disney animation characterised by feisty princesses

whose adventurous spirit could not be tamed (Belle in Beauty and the Beast, and Ariel of The Little Mermaid come to mind). While this may be so, the

narratives of these films are still characterised by the motif of romantic love,

and impossible stereotypes of idealised, chivalrous men. Narrative resolution only

occurs in these films when the princess secures a relationship with the prince

of her dreams.

What I want to suggest is

that far from a straightforward subversion of harmful gender stereotypes and

narrative motifs, Frozen actually

propagates a slate of contemporary ones that are quite reflective of the kinds

of gender inequality that exist today.

At the outset I would like

to acknowledge the fantastic plot twist whereby the act of true love needed to

save Anna, ostensibly the films principle heroine was not a kiss from her

prince but rather an act of self-sacrifice to save her sister. The film

explicitly flags this resolution as act of narrative subversion much earlier in

the film. Anna, having been accidentally wounded by Elsa during an ill-fated attempt

to reconcile, seeks the kiss of her true love Hans to save her from certain

death. As Hans slowly leans in to kiss the ailing Anna, he pauses, pulls back

and reveals that he cannot save her because he does not love her. Indeed, he has

deceived Anna into loving him so as to become king. After this startling

revelation, he promptly leaves Anna for dead.

It is Hans’ cold

manipulation of the hapless Anna that foregrounds my key problem with the film;

that is, the replacement of negative female stereotypes with negative male

stereotypes. Let’s take a closer look at our four key male characters.

King, father of Elsa and Anna

Once informed that Elsa’s

powers will grow and could be potentially detrimental to the kingdom, the King

effectively imprisons his young daughter. She is denied supportive

relationships and taught to bury her emotions so that they will not negatively impact

upon others. His failure to seek guidance and mentorship to help Elsa through

this difficult phase of childhood development is ultimately neglectful, yet the

film does not really draw attention to him as a harmful figure in Elsa’s life.

He is merely a plot device to catalyse the narrative, a stopgap that once removed,

unleashes terrible misfortune upon his kingdom.

The Duke, the evil capitalist

The Duke is another one-dimensional

character that largely serves the function of red herring, prompting audiences

to assume that he is the villain of the piece. This tiny leader of Weasel town

is clearly only interested in exploiting trade relations with the kingdom for

its own profit. He is in this sense, an embodiment of what feminists like to refer

to as patriarchy, embodied in the image of middle-aged white men who govern the

economy for their own benefit, and to the detriment of unsuspecting and

benevolent women. The physical rendering of this character, combined with his

capitalistic motivations, certainly embodies this villainous image of

patriarchy.

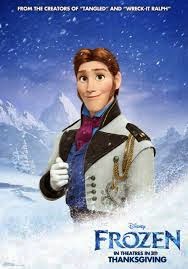

Hans, the upwardly mobile Prince of the Isles

Early in the film Hans is

the embodiment of the noble prince desired by princesses everywhere. He is

however another fairly under developed character allowing for the plot twist

exposing his conniving, self-interested and heartless character. This is not in

itself a problem, every Hollywood plot needs a villain to keep the drama

rolling, and as stated above, Hans is key to blowing apart the myth of romantic

love and unrealistic expectations of masculinity. Hans however, also serves to

round out a stable of negative male characters that tell us that: man + power = evil.

|

| Prince Hans |

|

| Kristoff |

Kristoff, the disposable male

With Kristoff we come to the

hero of the piece. Kristoff is humble and hardworking member of the working

poor. This is clearly indicated in a sequence when he unsuccessfully haggles for

basic supplies. His massive and muscly stature implies that he must engage in

difficult manual labour to earn the pittance that he lives off, this is also

indicated in the opening sequence representing the hard labour required to

harvest blocks of ice, Kristoff’s stock in trade.

Kristoff’s benevolent

humility is reiterated via his interactions with Anna, whereby he regularly assumes

his proper place below Anna in the social hierarchy (as both male and working

class). For instance, when Anna prematurely rushes to scale the mountain,

Kristoff who is more knowledgeable about achieving such a task, hangs back and

waits for her to realise that she needs his help. This reminds me very much of old

US family sitcoms where the obedient wife, who the audience recognises as more

knowledgeable than the domineering husband, waits for him to come around so

that she can dispense her expertise in an unassuming and non-threatening manner.

Most pertinent however, is

that Kristoff very much conforms to what Karen Straughan has termed “the

disposable male.” An evolutionary psychologist, Straughan posits that men have

predominantly come to be valued in society only insofar as they are willing and

able to sacrifice themselves for the benefit of women and society. Kristoff

regularly engages in acts of self sacrifice, for instance, when he sacrifices

his own happiness and delivers Anna back to her “true love” Hans to be healed,

and also, when he places himself in danger and helps her track down Elsa.

Sacrifice, as a

demonstration of male worth, is one of those under-acknowledged phenomenon’s

that abound in everyday life. Think for instance of celebrations and memorials

for war heros who have sacrificed themselves for the good of the nation-State.

Think also of the fact that it is men who are expected to assume more difficult

and strenuous forms of manual labour, detrimental to their long-term physical

health. That men have come to fulfil these roles is largely a part of human

evolution; humans are dimorphic, and men are for the most part, the naturally

stronger gender.

However, in contemporary

Western cultures, where it is assumed that democratic freedoms have liberated

humans from the shackles of biology and enabled everyone to craft their own

destiny, men - like women, the disabled, homosexual, transgender, black ethic

and other minority peoples – are in actuality, limited by enduring economic

constraints and social prejudices.

Contemporary understandings

of gender inequality, largely influenced by decades of feminist activism, tend

to obscure the ways in which many men are also constrained by social norms.

Think, for example, of campaigns calling for economic inequality that focus on

women’s access to corporate leadership roles rather than the ability to work

side-by-side with men in sewerage treatment plants or on the military frontline.

That Kristoff is the only positive

(human) male character in Frozen contributes to the widespread misapprehension

that the only good men in society are those that are willing to sacrifice their

lives and wellbeing for the common good.

This I think is the key

problem with Frozen. In line with

current social trends, the film’s attempt at gender subversion is mired in the

misconception that women are singularly disadvantaged by cultural

representations. The lack of critical attention to forms of gender inequality

that also effect men just creates a situation in which the pendulum swings the

other way, and women become blind to the specific ways in which they are privileged by

their gender. And this is detrimental to BOTH men and women. What will girls

gain from unrealistic perceptions of men as subservient, expendable or evil?

Like the trope of prince charming and true love dispelled by Frozen, these misconceptions of masculinity

do not inform the pursuit of meaningful and equal relationships, but rather,

continue to fuel unrealistic expectations of men.

Comments

Post a Comment